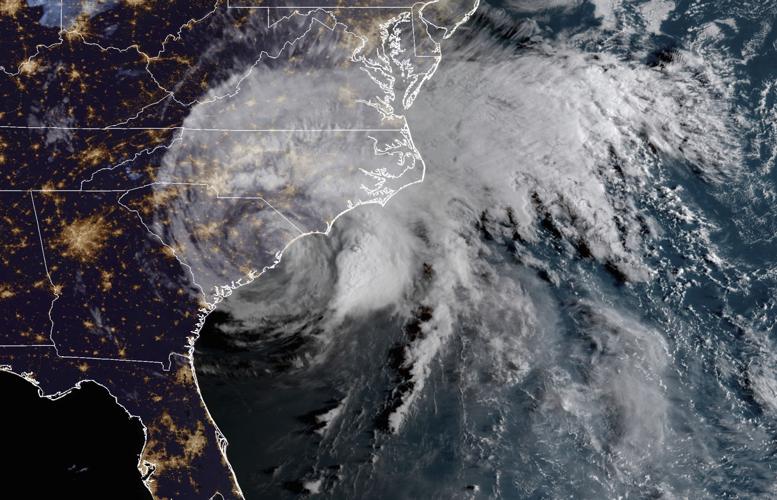

When Hurricane Florence hit South Carolina in 2018, it dropped nearly 2 feet of rain over its oddly long life. The flooding that ensued washed out entire communities.

Now, researchers might have a better idea of what fueled Florence. The “Brown Ocean Effect” occurs when tropical systems pass over waterlogged ground. It could provide important lessons on how future hurricanes that strike the swampy Southeast behave.

Hurricanes require warm ocean water to form and evolve from low-pressure systems into full-blown tropical storms. That’s why they typically lose steam when they hit dry land. But the Brown Ocean Effect proposes that a muddy, wet landscape could provide another fuel source for tropical systems, giving them a second wind that extends their life.

“The damage and the flooding that was caused by Florence was not characteristic of the typical damage we expect from a lower-category storm,” said Dev Niyogi, a professor at the University of Texas at Austin and a co-author of a study examining the Brown Ocean Effect’s influence on Florence.

The 2018 storm made landfall as a Category 1 storm, but brought a record level of rainfall to the Pee Dee which caused $607 million in damage in South Carolina, according to the National Weather Service.

“So, in other words, there was something else that must have been at play for Florence to have been so powerful and to have retained so much moisture,” he added.

Niyogi said researchers still have a lot to learn about the Brown Ocean Effect. For example, why doesn’t every storm that passes through the muddy Lowcountry experience the same effect?

More research needs to be done to see whether climate change and the Brown Ocean Effect interact in any way, he said. Last year was the hottest on record for the Earth, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration predicts a 99-percent probability that 2024 will also rate among the top five hottest years.

Even days after Hurricane Florence floodwaters inundated homes in the Rosewood neighborhood in Socastee on Sept. 28, 2018, standing water remained.

That warming climate is contributing to global ocean heating, which could super-charge hurricanes across the globe.

Rethinking Saffir-Simpson

J. Marshall Shepherd, director of the University of Georgia’s Atmospheric Sciences Program and an expert on the Brown Ocean Effect, said Florence and other Brown Ocean-influenced hurricanes reveal the flaws of relying too much on the Saffir-Simpson Scale. Ranging from Category 1 to Category 5, the scale is the most common measurement forecasters use to convey hurricane risk.

“The Saffir-Simpson scale is a wind scale,” Shepherd said. “It was always designed to talk about the wind hazard of a hurricane. But we know that the deadliest aspects of a hurricane are water, whether it’s storm surge or even freshwater flooding.”

Shepherd said that the National Hurricane Center, a sub-agency of the National Weather Service, has been experimenting with dynamic “impact-based” maps that more accurately convey the risk of a storm in recent years. But they’ve been slow to catch on with local weather forecasters and the broader public, he said.

“I increasingly preach the mantra that we need to focus more on the impacts with storms more so than their category,” he said. “Because you’ll often hear people say — you probably had some people say it with Florence — ‘Oh, it’s just a Category 1 or just a category this or that.’”

In an emailed statement NHC Director Michael Brennan largely concurred with Shepherd. Brennan wrote that the agency has tried to “steer the focus toward individual hazards” like storm surge and rainfall, instead of focusing too much on the category of a storm.

“Most deaths in tropical cyclones occur not from the wind but from water — storm surge, rainfall/inland flooding, and hazardous surf — causing about 90 percent of tropical cyclone deaths in the United States,” Brennan wrote. “So, we don’t want to overemphasize the wind hazard by placing too much emphasis on the category.”

South Carolina’s 2023 hurricane season was relatively quiet, largely due to the calming effect of El Niño — a cycle of warming in the Pacific that suppresses Atlantic hurricane activity.

But the Atlantic basin as a whole was extremely active, according to Shepherd and NOAA. There were 20 named storm events in the Atlantic basin in 2023, six more than the annual average.

Shepherd forecasts the 2024 hurricane season will be a rough one for the Southeast. NOAA predicted in December 2023 a 55-percent probability that El Niño will transition to La Niña this summer, which amplifies Atlantic hurricane activity.

“The water temperatures in the North Atlantic, even right now, are just off-the-charts hot,” he said. “I hope, I pray that this is a forecast that I’m wrong about. But I don’t think so.”

The Atlantic hurricane season begins June 1 and runs through Nov. 30.